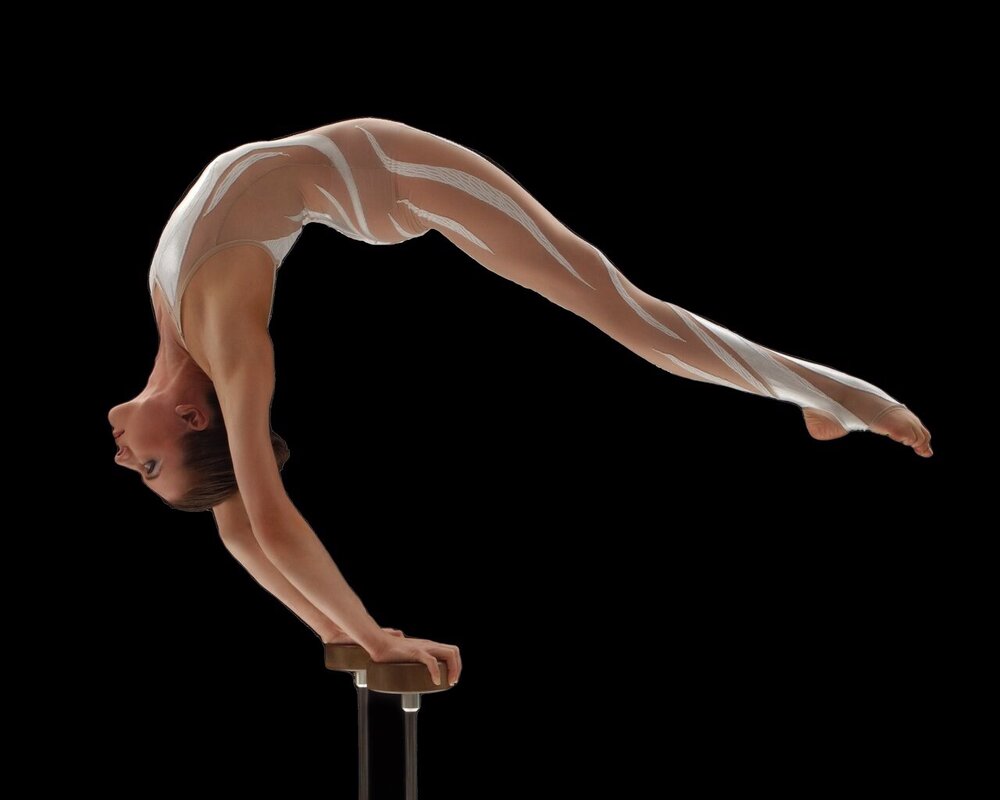

THE ART OF FLEXIBILITY—STRETCHING TECHNIQUES SCIENTIFICALLY EXPLAINED.

Let's explore the basis of the most effective stretching techniques that are the core of the Physical Poetry technique. There are thousands of ways to stretch. In this article, we explain the most efficient ones and we explain why.

ISOMETRIC STRETCHING

Isometric stretching is a static stretching involving muscular tension. While performing a stretch, you apply resistance with the same muscle groups you are extending. For example, while you are in a full split, you push against the floor under you, as if you wanted to close your legs through the floor.

You can use any static object for resistance. Alternatively, you can apply resistance to your own limbs—stretching your hamstring muscle by holding your foot is an example—pulling and pushing—or have a partner do so.

It is essential to be well prepared before this type of stretch as there is an augmented demand on the muscles we focus on. Warm-up with strength training or cardiovascular training using the muscle groups you mean to stretch. Ideally, maintain your heart rate above 130bpm for a minimum of 10 minutes. When focusing on a smaller muscle group or if the muscle has been injured, do not apply a maximum contraction.

Here is an example of an isometric stretch:

- Get into the passive stretch.

- Activate the stretched muscle for 15 seconds (resisting against a static object or a partner).

- Relax the muscle for 30 seconds.

There is a sweet spot immediately after the tension is released when it's possible to gain an extra range of motion. If you miss it, I find the body already able to resist a subsequent push. Here's why.

The science behind the timing of isometric stretching

The Golgi tendon organ (GTO) is a proprioceptive sensory receptor organ that senses changes in muscle tension. It is located at the insertion of skeletal muscle fibres into the tendons. When a muscle is elongated, the muscle spindle—a proprioceptor in the 'belly' of the muscle—will create a reflex contraction to protect the body. It will also warn the brain that joints and soft tissues are in danger of being stretched too far.

If you stretch long enough, the GTO will take over and inhibits the muscle spindle to create the contractions, enabling deeper stretch. This reactive process is called the lengthening reaction.

The lengthening reaction is possible because the GTO's signal to the spinal cord is powerful enough to overcome the muscle spindles' signal telling the muscles to contract. In other words, the GTO overwrites the muscle spindle.

After a complete isometric stretching, the fibres you’ve extended may be unable to contract again due to this lengthening reaction. It explains the strange sensation you may experience after a deep isometric stretch: the muscles you just worked on are unable to contract and do even minimal work. For example, after stretching a middle split (grand écart), you find yourself unable to close your legs—your inner leg muscles cannot bring your feet back together. This weakening is usually a sign that your muscle fibres are retaining the new lengthened information. They habituate to their over-extended limit and allows you to keep increasing flexibility.

Amongst static stretching techniques, isometric is particularly effective since the muscles are activated (contracted) at a full range of motion. An additional perk: isometric stretching seems to reduce the amount of pain experienced during stretching.

Isometric stretching is the base of PNF stretching, my tool of excellence for an aesthetic (long lines, perfect form) and an effective, flexible body in motion.

PNF STRETCHING

Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF) is a more advanced form of flexibility training. It involves both stretching and contracting (activation) of a targeted muscle group to achieve maximum static flexibility. Numerous studies on elite athletes and non-athletes alike have proven to be the most efficient to enhance passive flexibility.

Physical Poetry technique highly relies on its benefits. I have adjusted the common PNF stretching through the years to better assist physical performers' reality and challenges. It delivers the best results when combined with an active flexibility action as explained in the following clinical study: Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching : mechanisms and clinical implications

‘PNF stretching is positioned in the literature as the most effective stretching technique when the aim is to increase the range of motion (ROM), particularly for short-term changes in ROM. With due consideration of the heterogeneity across the applied PNF stretching research, a summary of the findings suggests that an 'active' PNF stretching technique achieves the greatest gains in ROM, e.g. utilising a shortening contraction of the opposing muscle to place the target muscle on stretch, followed by a static contraction of the target muscle’.

PNF training is most practical with a partner, but there are great alternatives if one is doing it solo (see picture below).

Most PNF stretching techniques are limited to isometric contraction of the agonist muscles (push). Some also apply isometric contraction of the antagonist muscle (hold), contracting the opposite muscle group of those initially contracted and pulled. Regardless of the technique, you must relax the muscles for 10 to 20 seconds at the end of a cycle. I found it counterproductive to get out of the position entirely; therefore, I only release the stretch slightly, and that way, I am ready faster for the next round while giving my muscles a necessary break.

‘ACTIVE’ PHYSICAL POETRY PNF

- Get into stretching position for 10 seconds.

- Push against resistance for 10 seconds.

- Stretch (passive) the muscle group you just contracted for 10 seconds.

- Hold without assistance (active) for 10 seconds using the opposite muscle group.

- Repeat action #2 (push).

- Repeat action #3 (stretch).

- Relax for 10 seconds (20 if you are a beginner and need to acclimatise).

Repeat the cycle 3 times for each given area.

The science behind PNF stretching

As mentioned above, during an isometric stretch, when the muscle performing the isometric contraction is relaxed, it retains its ability to stretch beyond its initial maximum length. PNF also uses that sweet spot of vulnerability—caused by the lengthening reaction—and profit from this increased range of motion by immediately subjecting the contracted muscle to a passive stretch.

We now know that the isometric contraction of the stretched muscle (agonist) accomplishes several things and helps prepare the muscle spindle stretch receptors to accept a more significant stretch. During the opposite muscle contraction (hold action—antagonist muscles activated), many fast-twitch fibres of the contracting muscles become fatigued and create additional relaxation of the primary stretched muscle group. As a result, the muscles are further inhibited from contracting against a subsequent stretch that could occur post-voluntary contraction. Hence the validity of the added antagonist contraction (active hold) that characterises the Physical Poetry method.

I practice this stretching technique to gain flexibility. I use simple passive stretching for rehabilitation or cool down. Stretching to increase flexibility should not be relaxing; it should be a committed practice that is highly energy-consuming. When performing a PNF, you must focus on the action and rely on your body's feedback: do not apply resistance if your extended hamstring is 'screaming' in pain.

Although I tried to summarise the essential facts, I am aware this is a lot of information. Let me know if you would like me to give more examples in a future newsletter or if there are any points you’d like to be clarified.

*This document is not a substitute for medical advice. You are responsible for your health. Consult a health care professional before using any of the techniques in this document.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.