THE CRUCIAL ROLE OF FASCIA FOR YOUR FLEXIBILITY (PART 1)

Fascia—from the Latin word 'band'—is a sheath of connective tissue that envelops the body underneath the skin. The fascia covers muscles, tendons and other mechanical linking structures like ligaments and flattened muscle-tendon units while separating it from subcutaneous tissue components (adipose tissue, neurovascular, mechano- and proprioceptors of the skin) [2].

At a micro-level, the fascia consists of collagen type I and III fibres and, to a lesser degree, elastic and reticular fibres, fibroblasts (a type of cells that contributes to the formation of connective tissue), and water-binding ground substance, helping attract and retain water for structural purposes while also providing flexibility to organs and tissue [3,7].

The role of fascia is often underestimated when it comes to flexibility and injury prevention. A lot of us even ignore its presence and importance in movement science. Since there is so much to cover, we divided this article into two parts: In PART 1, we cover the fundamentals of fascial tissue and how their condition can affect your health and mobility. In PART 2, we explain how to stretch and promote a healthy fascia.

FUNCTIONS OF FASCIA

The fascial system has almost no discontinuity in its path. It allows the human body to maintain its regular shape at its resting position. Furthermore, it supports the specific mechanical needs of different body regions, such as keeping the right amount of tone, elasticity, and stiffness. It also plays a role in coordinating muscle movements and prepares the nervous system for action by recruiting neurons and enabling synchronised muscle contractions. We have a superficial fascia (closer to the skin) and a deep fascia (closer to the muscle fibres) [2]. The superficial fascia may be more related to temperature regulation and energy storage. In contrast, deep fascia helps compartmentalise the body, forming sheaths around muscle groups and promoting an optimal transmission of the forces generated by muscular movements, translating to an efficient function.

FASCIA REMODELLING

Fascial tissue constantly react to everyday strain and specific training, steadily remodelling the arrangement of their collagenous fibre network. For example, as you walk, the fascia of the outside of your thighs develops more firmness than the fascial tissue on the inside. The opposite would happen if you were constantly straddling a horse. In a healthy body, this remodelling process takes about a year to replace half of the collagen fibrils or about two years for total remodelling [5].

In PART 2 of this fascia blog series, we will detail how to promote the remodelling of the collagen network through different types of movement. Our goal is to empower you to stimulate fascial tissue precisely to achieve a healthier structural arrangement of the collagen network, helping the body maintain flexibility and prevent pain disorders.

DOES AGEING AFFECT THE FASCIA?

A healthy fascial network has a bidirectional lattice arrangement, similar to a woman's stocking, with two-way stretching abilities. As we age, we usually lose the springiness in our walk, and as a result, the fascial architecture takes on a more disorganised and multidirectional fibre arrangement [5].

Besides the arrangement of the fascial network, studies have found that an increased fascial thickness in older people is associated with reduced flexibility compared to the thickness of young, healthy adult fascia [9].

There is also a difference in the lubrication found separating the different fascial layers. Fascia contains high concentrations of hyaluronic acid, which functions as a lubricant. However, in the absence of exercise and loading in a more sedentary ageing population, the substance becomes more viscous and the gliding of the fascial layers is restricted. This results in a higher concentration of sticky hyaluronan and increased connective tissue thickness leading to decreased flexibility [9].

FASCIA AND PAIN

Pain originating from the deep fascia likely results from increased nerve density, sensitisation and chronic nociceptive (pain nerve receptors) stimulation, whether physical or chemical. Changes in innervation, immunology and tissue contracture characterise an altered fascia [4,6]. Micro-tearing and fascia inflammation can also be a direct source of musculoskeletal pain. Studies have even found a reduced elastic capacity of fascial tissue in people who suffer from low back pain [8]. Hence, fascia may be an indirect source of back pain due to the triggering of fascial nerve endings. They, in turn, initiate inflammatory processes in other tissue within the same segment. This secondary inflammation process is not limited to back pain; it could come from chronic neck pain, plantar fasciitis, and iliotibial band syndrome (which causes knee pain).

Fascial tissue inflammation is usually due to overuse injuries, primarily from a repetitive strain causing micro-tears. Once more, we are reminded of the importance of adequate recovery time and healthy training techniques to avoid such overuse injuries. For more information and prevention tips, refer to our articles HOW TO REDUCE MUSCLE SORENESS AND SPEED UP RECOVERY and OVERTRAINING AND INJURIES.

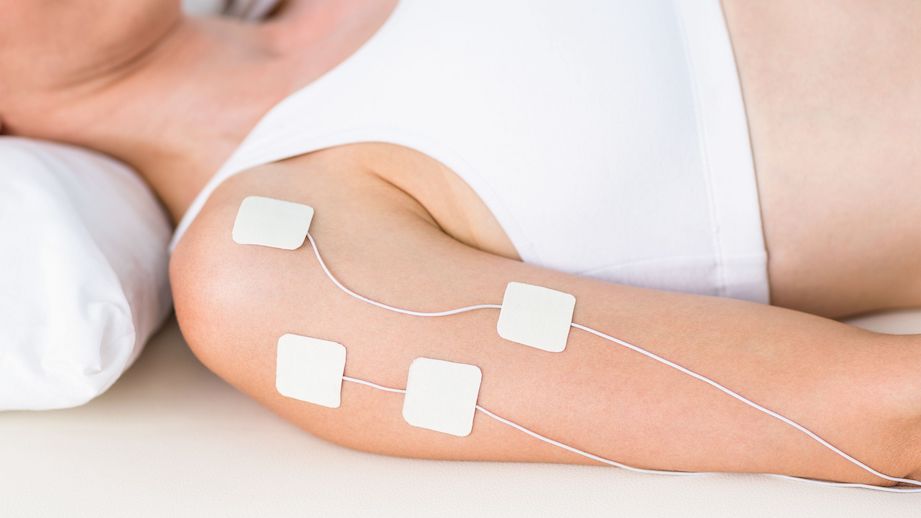

MYOFASCIAL RELEASE TREATMENT

Myofascial release (MFR) is a widely employed manual therapy treatment that applies guided, low-load, long-duration mechanical forces to manipulate the myofascial components. The goal is to restore optimal length, decrease pain, and improve function. By promoting the restoration of length and health of restricted connective tissue, strain can be relieved on pain-sensitive structures such as nerves and blood vessels.

MFR typically requires sustained pressure (120-300 seconds) applied directly (direct MFR technique) or indirectly (indirect MFR technique) to the restricted fascial layer. Direct MFR technique works straight over the restricted fascia: practitioners use knuckles, elbow or other tools to sink into the fascia slowly. The pressure applied is a few kilograms of force to reach the restricted fascia, apply tension, or stretch the fascia. On the other hand, indirect MFR involves a gentle stretch guided along the path of least resistance until free movement is restored. The pressure applied is a few grams of force, and the hands tend to follow the direction of fascial restrictions, hold the stretch, and allow the fascia to loosen itself [1]. Myofascial release treatment might be an effective treatment option, especially when the pain is already present.

FINAL THOUGHTS

We have just covered a lot of information. In conclusion, fascia is a remarkable and often overlooked connective tissue that plays a significant role in our body's flexibility, movement, and overall health. Understanding the composition and functions of fascia is essential for optimising our flexibility, preventing injuries, and maintaining mobility as we age. Embracing myofascial release treatment can further enhance fascial health and alleviate pain. By appreciating the importance of fascia in our body's complex systems, we empower ourselves to take better care of our physical well-being and achieve a more flexible and pain-free life.

Stay tuned for PART 2 of this Fascia series; we will discuss specific exercises and practices to benefit your fascial tissue.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.